I was shopping for socks when I noticed this sticker on a package: “$5.25 per each.” Per each? I resisted the temptation to cross out “per” and wandered away wondering why that phrase sounded wrong. Had the sticker read “$5.25 each” or “$5.25 per package,” I wouldn’t have given it a second thought. “Per” is a preposition and requires an object. So why not ” each”? When I got home (minus the socks I was shopping for, having spent the whole trip thinking about the preposition), I looked up the definition of “per,” which is “for each.” So the sign actually read “for for each.” I did consider the possibility that the total cost of each pair was $10.50, with $5.25 being the price of one sock. But surely the average consumer does not expect to pay for each foot separately? No, I concluded. This was an example of the “more is more” theory of writing.

Here’s another:

I should mention that the store did not offer “dry cleaning” services, just laundry. And what else would you do with laundry – dirty it? lose it? (Okay, sometimes a store does “dirty” or “lose” the laundry, but not on purpose.)

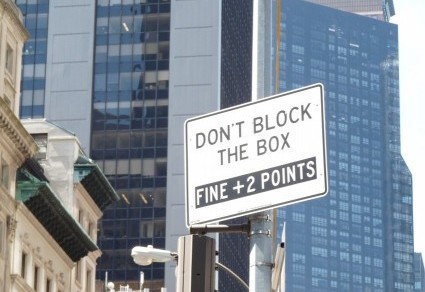

Here’s another sign:

As all fans of British television series know, “chemist” is the British term for “pharmacy.” So this shop is a “pharmacies pharmacy.”

Personally, I still hold that “less is more” in writing, as long as the meaning comes across clearly. I’m not sure why so many people subscribe to the “more is more” style. Maybe the clutter of modern life gives rise to the fear of being overlooked, and that a second (or third) repetition lessens that possibility?

Your theories are welcome welcome welcome.