Some years ago, while I was teaching Elizabeth Bishop’s poem “The Fish,” a student stumbled over the proper term for the person who caught the animal. He started out with “fisherm…” and then stopped himself and went with “fisherperson.” Fisherperson? Really? I consider myself a feminist, but even I was taken aback by this word. It was fair, of course, because both men and women go fishing. But it sounded like something a late-night television host would mock. Yet what is the alternative? Fisher? Trout-worker? Marine life catcher? Perhaps letter carrier and firefighter also sounded strange when they first entered the language in place of postman and fireman.

I thought about this issue when I saw this sign on a construction project:

Only men work there? Or are only the male workers dangerous? Neither meaning is likely, so the sign is incorrect. The habit of assuming that a male term is understood to include both men and women – the “masculine universal” – has been out of favor, and for very good reason, for many years. Yet “MEN AND WOMEN WORKING ABOVE” seems artificial. How about “DANGER: CONSTRUCTION ABOVE”? Or, “WATCH OUT! WE’RE WORKING UP HERE!”

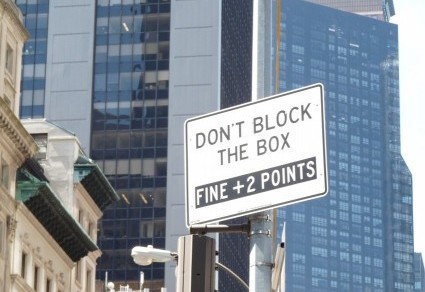

Here’s another sign:

Okay, busboy doesn’t work, not least because some of those doing this job are a couple of decades past boyhood (or girlhood). I can’t really support busser, as buss is a slang word for “kiss.” Table cleaner isn’t accurate, nor is plate remover. So, I’m stumped. Any suggestions?

The larger point is that language changes slowly, especially when it’s tied to a social movement, in this case feminism. And yes, gendered language matters. Children asked to draw a scene with cavemen hardly ever include women, while those asked to draw cave people more or less balance the sexes. So we do need these changes if we’re to see possibilities and eventual equality. Along the way, though, we may have to deal with some fisherpeople.