Like a squirrel hoarding nuts, I’ve been stockpiling a few mysterious signs, hoping that at some point their meanings will emerge. These signs, all from shops selling food, defeat and delight me. I offer one or two interpretations and invite you to add your own commentary. First up is this beauty, which appears on a chalkboard in front of a hip (i.e. overpriced) restaurant:

I prefer maximal, myself.

My interpretation: You may find a grain or two (sand? wheat? spelt?) in the food, but grainophobes have nothing to fear here. Same restaurant, different sign:

Bring a lasso.

My interpretation: The loaf lopes around the dining room. If you can catch it, you can eat it. Or, the loaf parties all night and won’t follow any rules.

One more, from a different store:

Two-foot ceilings?

My interpretations: This shop (a) sells neatly ironed, fruit-based beverages or (b) was a normal- height building before King Kong’s foot flattened it.

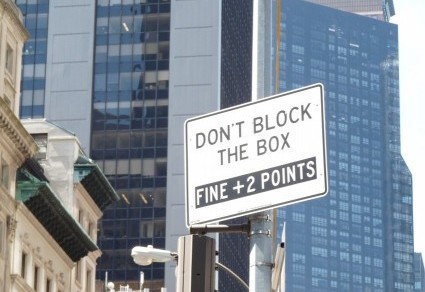

Your ideas are welcome. As you interpret the meaning, though, keep in mind that these signs appear in New York City, which may be defined as having a

Oh, yes we do.